|

|

RAMBLING DOWN HIGHWAY 395

July 2005: A journey from Lake Tahoe to Mt. Whitney

Wright's Lake

An afternoon paddle at our first stop—Wright's Lake—a small jewel hidden in the mountains, up a long and rough road to the north of Highway 50. In the background, gateway to the Desolation Wilderness.

Paddling out of a narrow and twisting channel, barely wider than the kayaks, a second small lake reveals itself amid the trees.

Quiet waters; a mountain home for ducks. No wind to rustle the trees—just the low buzz of mosquitoes. To the north is a third lake, no more than a watery marsh with a narrow and deep channel—so narrow that we have to back the kayaks out.

Lake Tahoe

On to Lake Tahoe. Arrived in time for an afternoon paddle along the South Shore. A little breezy and choppy to start, but as afternoon gave way to evening, both water and wind turned calm. A hot day called for a cooling swim before dinner.

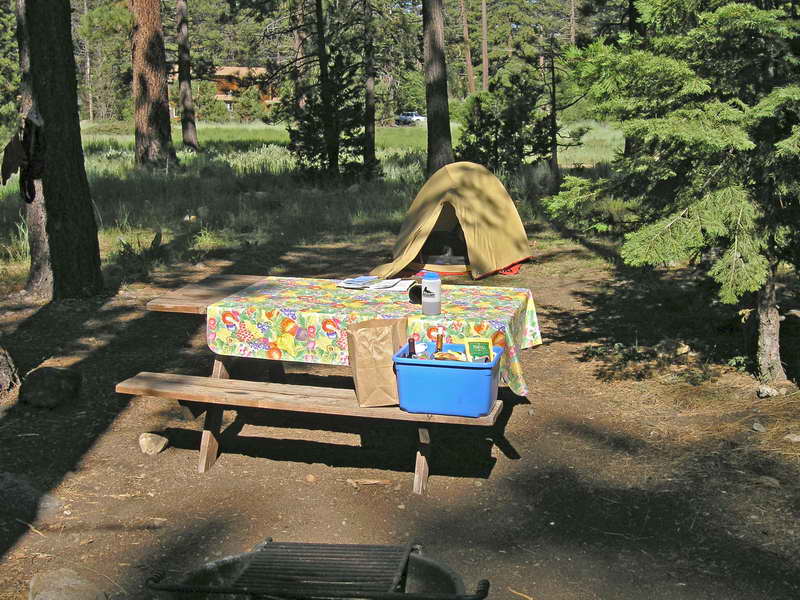

Spent the night at the private Camp Richardson. Looked into the state parks along the southwestern edge of the lake, but we were unimpressed with the sites—too far from the water or no flat patch of ground large enough for even a small tent.

Fallen Leaf Lake to Aloha Lake hike; a steady climb up though the lower forests. Sunny and very warm, but almost no one sharing our trail.

Susie Lake, about 7,800 feet in elevation and about four miles up the trail.

Postcard setting of a Sierra alpine lake. Cool, crystal-clear water, fine on the toes. Watched over by Jack's peak, 9,856 feet.

The outflow for Susie Lake. A lovely noise of water flowing over rocks and logs.

Carefully crossing the outflow—the logs cross deep and watery holes. The breezes have created rafts of yellow pollen.

Skirting Heather Lake; it's more exposed and less inviting than Susie Lake.

Some brilliant color among the mass of gray boulders.

The occasional snow patch covers the trail. Hard, old snow, it's easier to walk around it. The mosquitoes attacked on our way back down, driving us nearly mad by the time we reached Fallen Leaf. (We unfortunately left the Deet back at camp.)

Long view of the way up to Aloha Lake. Off in the distance is Grass Lake and beyond, the peaks above Lake Tahoe, to the east.

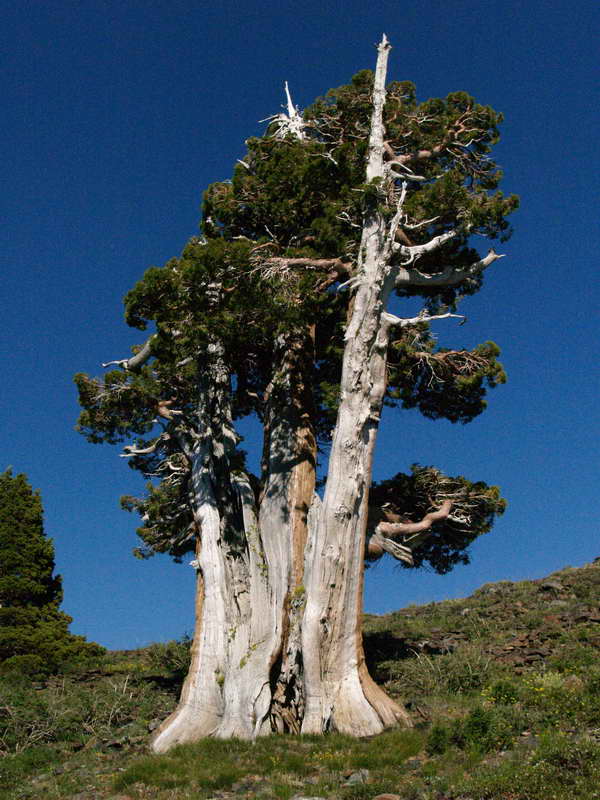

Solitary giants, ancient Junipers out-survive competing species at tree line.

Our destination: Aloha Lake. At 8,100 feet, it marks the eastern fringe of the Desolation Wilderness area. It's a bit over five miles and 1,460 feet of climbing from the trailhead near Fallen Leaf Lake. A fabulous hike.

Aloha Lake panorama. More water than usual for July. Often, by mid-summer it is a series of ponds. A perfect day: no wind, no clouds, just pure sun.

Bodie

With Lake Tahoe in the rear-view mirror, we started our trek south on Highway 395. Just north of Mono Lake and the eastern entrance to Yosemite, the ghost town of Bodie sits in the high and dry desert. A gold-rush boomtown established in 1877, Bodie is said to have had a reputation as the most dangerous town in California.

Desert blooms, fields of Prickly Poppies.

Large blossoms—approximately four inches across.

Bodie baking in the morning sun. A state park, it's best to take in Bodie early in the day—the crowds arrive in late morning, taking away some of the ghost town atmosphere.

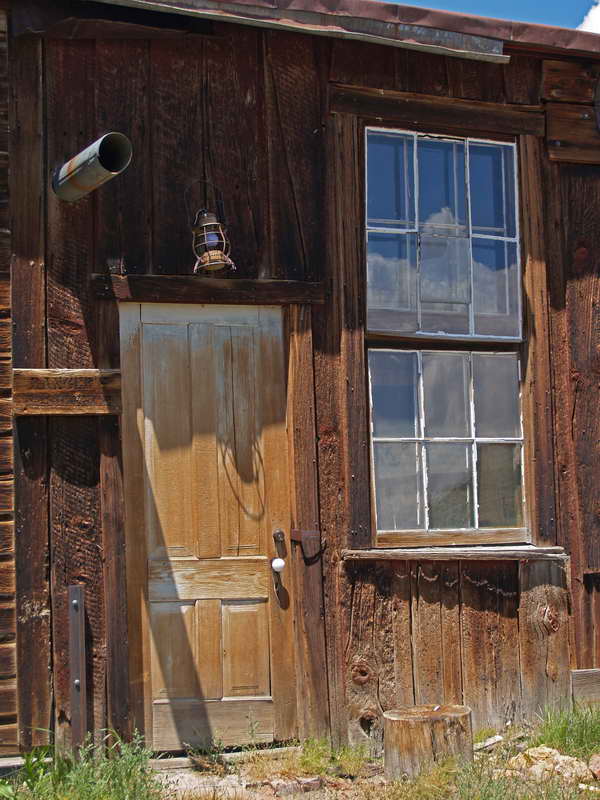

James Cain House. The buildings of Bodie are kept in "arrested decay"—most have new roofs to keep out the weather, and enough restoration to keep them standing.

Hoover House, standing on the eastern hill overlooking Bodie and next the large metal-stamping mill structure.

After the saloon, the second-most important building in a mining town—the bank. All that's left is the vault—inside another smaller safe.

Beauty in ancient doors and windows.

The Methodist Church. Inside, the pews remain waiting for a lost congregation.

Mono Lake

East of Yosemite is one of the oldest lakes in North America. Mono Lake has no outlet and a salinity that is more than twice that of the sea. Its waters were once sucked away for Southern California cities. But no shortage of water this year. The lake looks full and healthy.

Kayaking the calm waters of Mono on a hot day. The launching site, Navy Beach is at the south end, down a long dirt road. The salinity makes the kayaks especially buoyant. Salt flies coat the shore along the waters edge and they move from underfoot as you walk into the water. Fortunately, they stay on the ground and do not bite.

Tufa columns dot the lake, well out from shore. About 15 to 20 feet tall, these towers of minerals are favored by Ospreys as safe nesting sites.

A mother Osprey returns to her nest.

A tufa island stands in water that's only a foot or two deep.

Reflections of earth, sea, and sky.

Tufa towers near shore. A trail winds on the other side, but they are more interesting when seen from the water.

Above and below—just enough water to float a kayak. Billions of brine shrimp cloud the otherwise clear water.

Mono Lake at its best. And a kayak is the best way to experience it.

No plans for the kayaks after June Lake. Spent part of the morning breaking them down and packing them back into their travel bags. The new racks we picked up in Tahoe worked like a charm— well worth a hot morning spent behind the sports shop mounting them on the truck.

The Mammoth area

Spent a night at the lovely June Lake and then made the short drive down to Mammoth Lakes. A spectacular ride up the gondola to the top of Mammoth Mountain. On the way up, caught sight of a small party of snowboarders riding old snow, followed by a Black Lab with—of course—a ball in its mouth.

Mammoth in mountain biker central in the summer. Take your bike up on the gondola and ride down trails from the peak. Looks like fun.

The San Joaquin River-Middle Fork near the Devil's Postpile. Again, most of the campsites taken but found a nice one near the river.

Minaret Falls along the Pacific Crest Trail. A beautiful cascade of water.

A sunny, warm, and very pleasant lunch spot along the San Joaquin River.

At Mammoth, the Pacific Crest Trail parallels the San Joaquin for miles. This day was a long, hot hike through the forests. Worn out by the time we arrived at another campground, we opted for the convenient shuttle bus to get us back to our campsite.

Along the trail, small clusters of delicate Penstemon

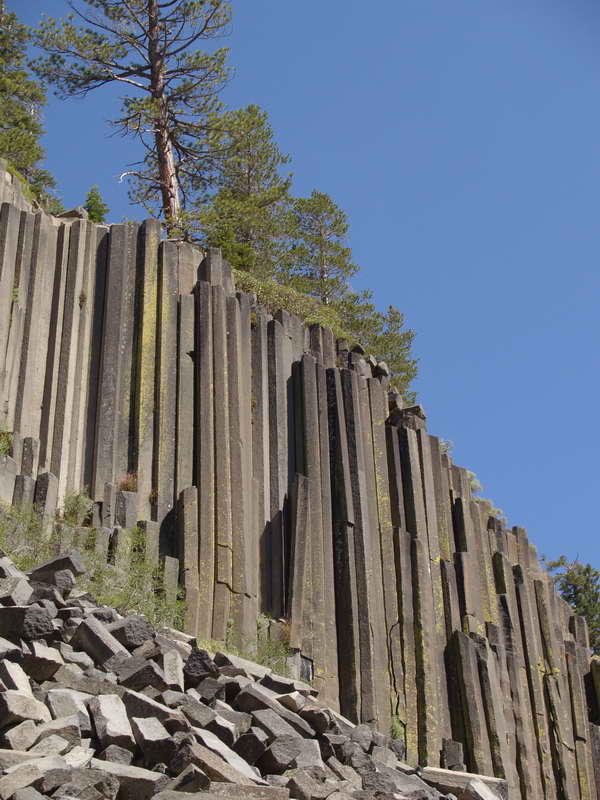

Devil's Postpile. Volcanic rock that cooled into crystal-like columns. Only a short half-mile up from the parking lot. Interesting natural phenomenon, but smaller than the tourist pamphlet photos suggest—perhaps 70 feet high.

Along the Devil's Postpile trail, a field of Shooting Stars.

Mammoth a riot of wildflowers, like most of the Eastern Sierra this year. Paintbrush adds a bright splash of color.

Lupine in profusion.

South of Mammoth along Highway 395, a chance detour up a rough dirt road to photograph striped mountain strata. The view no better than from the highway, but a fun test of the Toyota's four-wheel capabilities.

A patch of Paintbrush lights up the dull sage. Far in the distance, Crowley Lake shimmers in the high desert heat.

Another chance discovery—perhaps the best of the journey. South of Mammoth, off 395 at Steve's Place, up Rock Creek Road, a stunning trail passes through alpine meadows and lakes to the high Sierras. Along the way, we stop to chat with Conservation Corp trail workers moving rocks in the bright sun.

Hart Lake, along the Rock Creek Trail. A small jewel and favored spot for fly fishermen—women: a young couple with infant trade off fishing and baby-sitting duties.

Crimson Columbine flourishing along the creek.

Hart Lake from the west end. Mountains, trees, snow, blue lake and burbling creek—an unbeatable combination.

A blaze of Scarlet Penstamon lines the Rock Creek Road.

The White Mountains

After a scorching-hot drive through the towns of Bishop (not looking its best in the summer heat) and Big Pine, we turned east on Highway 168, headed for the ancient Bristle Cone pines. Arrived in the late afternoon to the relative cool of the high peaks.

The nearby Grandview campground is primitive—no water, pit toilets, and no rangers; but it's only three bucks per night.

Stopped a half-mile short of the Grove of the Patriarchs—a lone patch of old snow blocking the road at over 11,000 feet. The sun was rapidly setting behind the hills to the west, so we dashed up the nearest hillside of trees to catch the late sun.

In a dry land, even dead trees last for thousands of years.

Just a thin strip of bark is all a Bristle Cone needs to last through the worst of times.

Life turns to sculpture, shaped by centuries of wind, snow, and grit.

Bristle Cone candelabra.

Snag in fading light.

Another snag at dusk.

Day's end and a full moon rising in the east.

Morning above the Bristle Cone campsite. Glorious view across the Owens Valley of the Eastern Sierras and Mt. Whitney—our next destination.

Mt. Whitney

On the way to Whitney, we took a detour to explore the road up to Kearsarge Pass trailhead. It's a long, extremely twisty, and narrow road that ends at over 9,000 feet. Along the way, more Crimson Penstemon adds eye-catching color to and already bold landscape.

We run into some bold grouse on the lower half of the Whitney Trail. We had Passed through Lone Pine the day before and scored day passes without reservations. Almost no one on the trail—seemed odd for peak season. Felt like we had the mountain to ourselves.

A surfeit of running water on the Whitney Trail. Crossing a log bridge that's longer than most; in the shallow water, three- to four-inch long fish.

Outpost meadow at 10,000 feet on the Whitney Trail—the first (and infrequently used) campsite on the way to the highest point in the lower 48 states. But also home to the finest waterfall on the mountain.

The waterfall near Outpost campground. In November, it freezes into a massive sheet of ice.

Sparkling water and the roar as it crashes on rocks. A pleasant stop on the way up.

Above Outpost, Mirror Lake nestles between the peaks. From here, the forest thins to a scattering of hardy, solitary trees.

Wildflower accents along the stony trail.

Above 11,000 feet, a world of rock and light. Looking back on the way up to the high camp.

The gatekeeper—a marmot scampers to the top of his rock to see who's passing; and who will leave a snack as toll.

The final climb to the high camp at 12,000 feet. The trail becomes more treacherous—more interesting, more challenging, and far more fun.

Consultation Lake—one of the two bodies of water at the 12,000-foot camp.

Trailside Camp at 12,000 feet—a 3500-foot climb from the trail head. Trailside is the overnight camp for many Whitney climbers. Spent one of the coldest night of my life here, alone in mid-November, but today, a long-sleeve t-shirt was all that was needed while sitting by the lake, taking in the view and ice-cold water.

A dozen or so hikers spending the night at Trailside. After a week of hiking the Eastern Sierra, we are fully acclimatized—no heavy breathing this time. We regret not bringing full packs.

The way up from Trailside. It's two thousand feet and about a hundred switchbacks up the rocky slope on the far left-middle of the photo. From there the trail winds along the back of the sawtooth peaks (photo center)—past Mt Muir, the tallest, past Keeler Needle—for 2.5 miles to Whitney Peak (14,495 feet), hidden behind the large knob of rock, photo right.

Whitney Trail is a journey of endless views.